Jointly Learning Sentence Embeddings and Syntax with Unsupervised Tree-LSTMs

This series contains summaries of interesting papers.

Jointly Learning Sentence Embeddings and Syntax with Unsupervised Tree-LSTMs, by Jean Maillard, Stephen Clark, and Dani Yogatama.

This paper by Maillard, Clark, and Yogatama presents a TreeLSTM-based model that jointly learns to build binary parse trees and sentence representations to optimize for a downstream task. It’s a neural approach to grammar induction, and the authors present a fully-differentiable model, meaning it can be trained end-to-end on the downstream task.

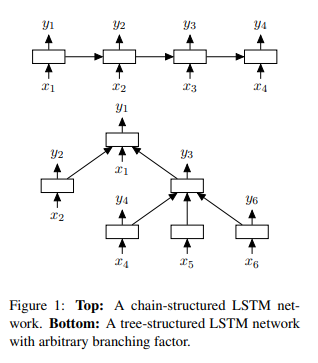

First, it would be useful to know about TreeLSTMs, which were developed in this 2015 paper by Kai Sheng Tai, Richard Socher, and Chris Manning. Standard LSTMs consume linear sequences of tokens, whereas human language has syntax and thus a latent tree structure. To take advantage of that fact, Tai et al. introduced a tree-structured LSTM. Each cell in the LSTM can have multiple children cells, as opposed to a single child:

However, the TreeLSTM has a crucial drawback: it relies on knowing the sentence parse a priori. To get around this, the authors introduce a model which can consider all possible binary parses of a sentence to compute a sentence embedding. It is a CKY-based model that uses a “differentiable chart parser” (more on this later).

They evaluate the model extrinsically on two tasks: (1) semantic similarity and (2) a “reverse dictionary task”. In a later version of the paper, they evaluate the trees intrinsically by looking at the (a) the model’s stability to random initializations and (b) the similarity of the trees to parse trees from the Stanford parser. Though this isn’t in the linked paper, I think it still bears at least a brief discussion because it’s an interesting way to do intrinsic evaluation.

Chart Parsing Model

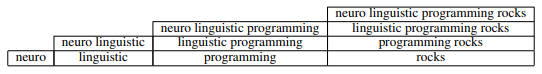

If you’re unfamiliar with CKY (or CYK) parsing, I highly recommend the Wikipedia page, which has a very nice visualization. A lower triangular matrix is used as a “chart”, which is capable of representing all possible binary compositions of the words and chunks that make up a sentence:

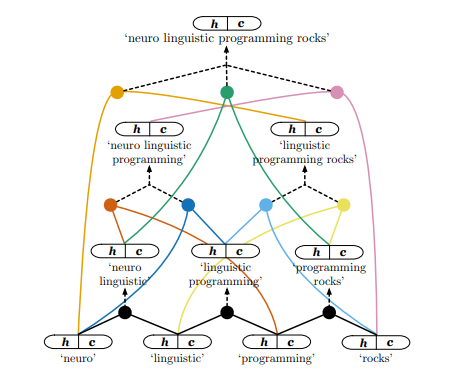

The model computes an LSTM hidden state (a (context, hidden) tuple), for each cell in the Chart:

The different candidate parses above the 3rd level of the model are combined with an attention mechanism. The model has a trainable vector that it can use to attend to a specific parse, and a decaying temperature is used to increase the peakiness of the attention.

Evaluation

In the linked paper, the trees are evaluated extrinsically on the SNLI task and the “reverse dictionary task”. The “reverse dictionary task” is basically: given the definition, retrieve the word from a set of possibilities (that includes confounders). They show that the model outperforms similar models with the same number of parameters, including Tree-LSTMs with fixed parse trees, but still performs worse than larger models.

The tree evaluations are quite interesting. First, they compare the maximum likelihood trees (taken via attention weights) with trees from the Stanford parser, as well as left-branching and right-branching trees. Second, they compare the trees of the same model trained with different random seeds, to compute a “Self-F1”. This second one is what I find most interesting, as it hints at a desired property of induced grammars: stability. To me, this implies that much like a large probability basin in Gibbs sampling or the flat minima (as opposed to sharp minima) that SGD is said to seek, an induced grammar might be more generalizable if it’s stable across model runs.